It’s fun to think about the future of biology and lab automation, and this is especially true today. We are witnessing exciting new developments supporting fully autonomous biology: new devices, new robotics platforms, and rapid progress in AI-driven discovery. But, as biologists, automation engineers, and lab managers know, turning this vision into a reality will require more than just new technology in the future—it also requires careful decision-making today.

As biologists and lab automation professionals, we’re at a moment where we must make decisions about potentially disruptive technologies, while meeting the needs of our labs in the present. The reality is that we still have goals to hit tomorrow, in six months, and later this year, regardless of what the future will bring.

In partnership with the Society of Laboratory Automation and Screening (SLAS), I gave a talk where I shared my thoughts on the future of biology and the practical steps biologists can take to get there. I’ll cover many of those ideas here, but if you’d rather watch the full conversation, you can view the webinar here:

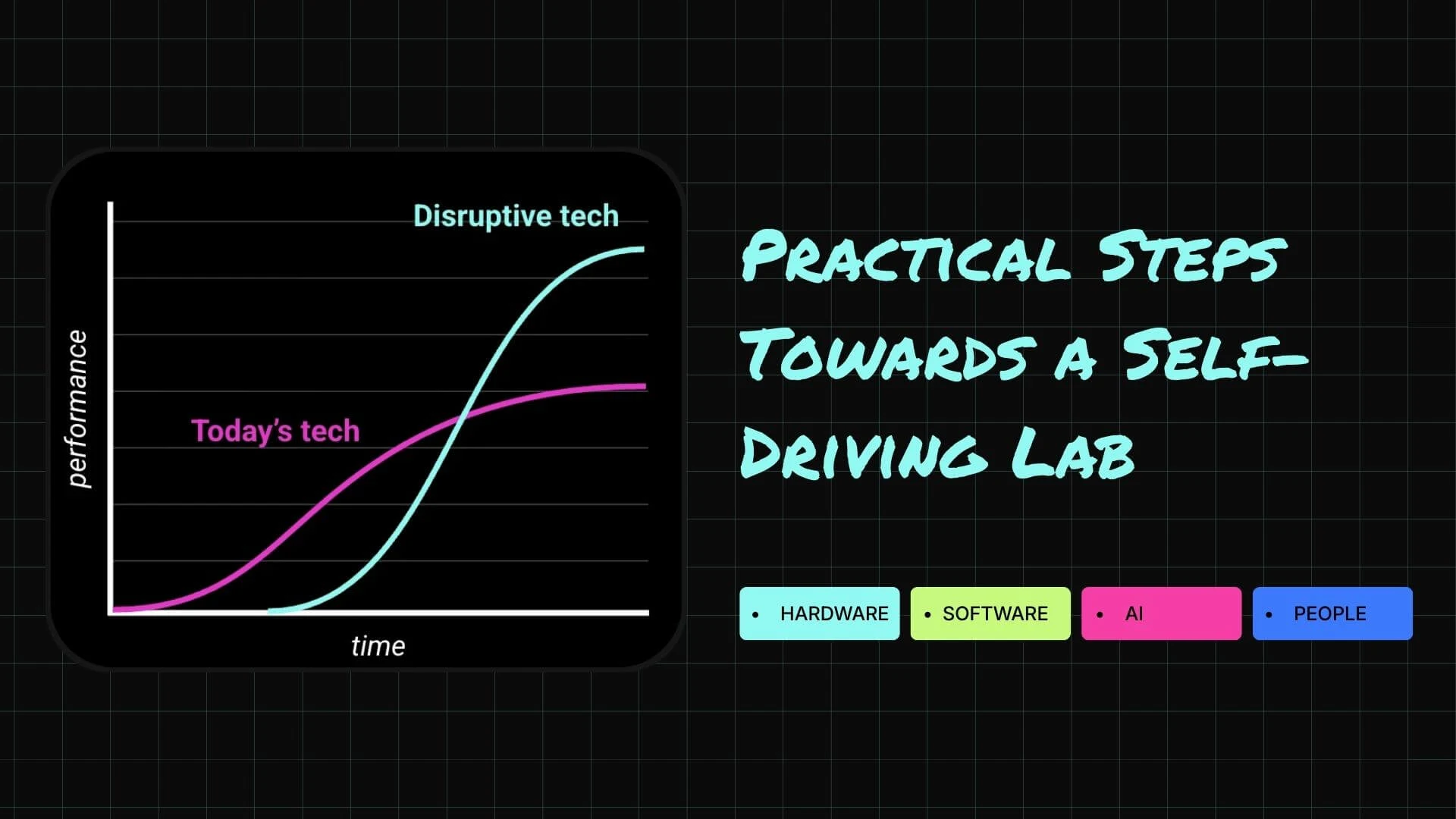

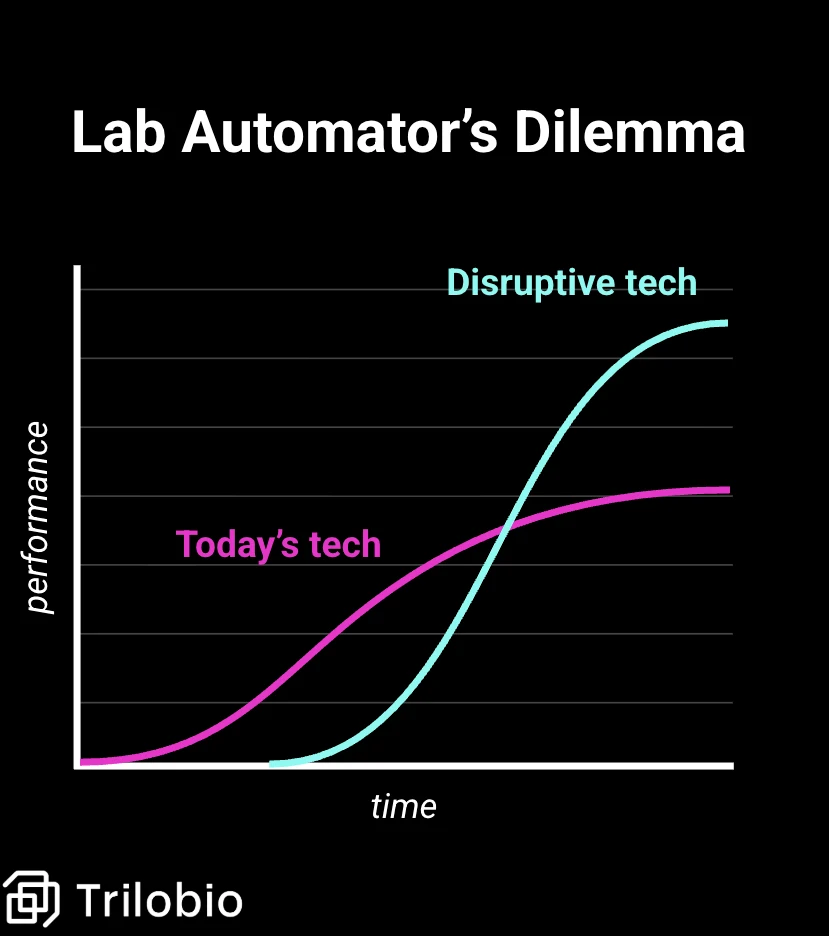

The lab automator’s dilemma

As we experience rapid change and the introduction of potentially revolutionary technologies, it becomes difficult to balance innovation and the real constraints most labs experience: limited resources, evolving priorities, and pressure to keep research moving forward. This is what I call the lab automator’s dilemma. How do we make the decision to invest in lab equipment if one option is cheaper but doesn’t support key future technologies, or another option that is more expensive but includes features that extend its shelf life into the coming AI-driven era?

This is the important balancing act biologists will be forced to make over the coming three to five years. On the one hand, there is an exciting, promising, shiny future of fully automated and even autonomous biology labs. On the other hand, there is the reality of the work that needs to be done today. To balance this, we need to create criteria and frameworks for making decisions about evaluating new technologies in the context of both current and future goals, and how we can future-proof our investments today to maximize long-term value and prevent waste.

Self-driving biology labs are the future of research

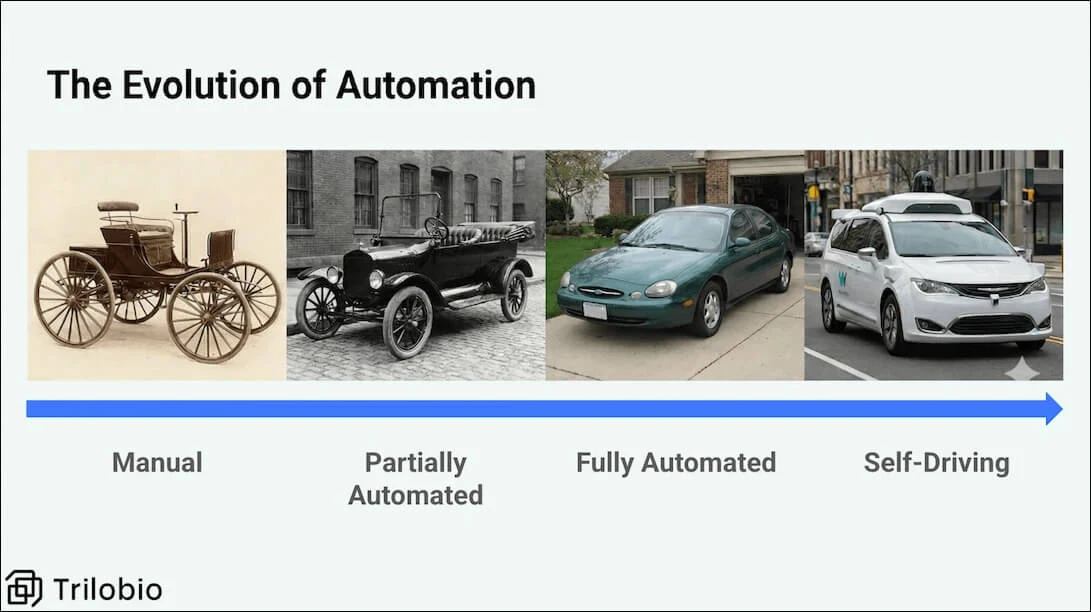

Across the industry, labs exist at very different stages of automation.

Some teams still perform most of their research manually, for reasons ranging from cost to the highly exploratory nature of their work. Others have automated individual steps in their workflows to reduce human error or increase throughput for specific functions. Some operate advanced, fully automated labs at the frontiers of biology and automation. And a small number are already working with closed-loop, AI-powered self-driving labs for biology.

So, what exactly is an SDL for biology? A self-driving biology lab—also referred to as an autonomous laboratory—brings together end-to-end full lab automation and AI-driven discovery to continuously run, analyze, and refine experiments. In this model, a biologist works with AI to set goals for the research and design protocols, but then allows the AI to iterate and adapt the research during execution in search of a target end-state. This closed-loop approach enables both large-scale data generation and faster biological discovery by making it possible to conduct research for a significant period of time without human intervention while leveraging AI to determine next steps based on data collection at various points of the research protocol.

The 4 pillars of self-driving labs for biology

If self-driving labs are the direction many teams are preparing for, it’s important to be precise about their distinct components. A self-driving lab is a closed-loop research workflow comprising hardware, software, artificial intelligence, and human input that creates an explosion of data production. Each component plays a critical role in the SDL.

- Hardware is the physical layer that executes the research. It must be able to run for long periods of time and support complex research workflows

- Software is the digital layer that connects and orchestrates the SDL. It must support the creation, execution, and documentation of protocols across many devices

- Artificial intelligence is the adaptation layer that iterates on protocol design by adjusting variables and incorporating data mid-cycle

- People is the human intelligence layer that guides and provides critical input to the SDL. Biologists will remain deeply involved, from experimental design to analysis and critical decision-making

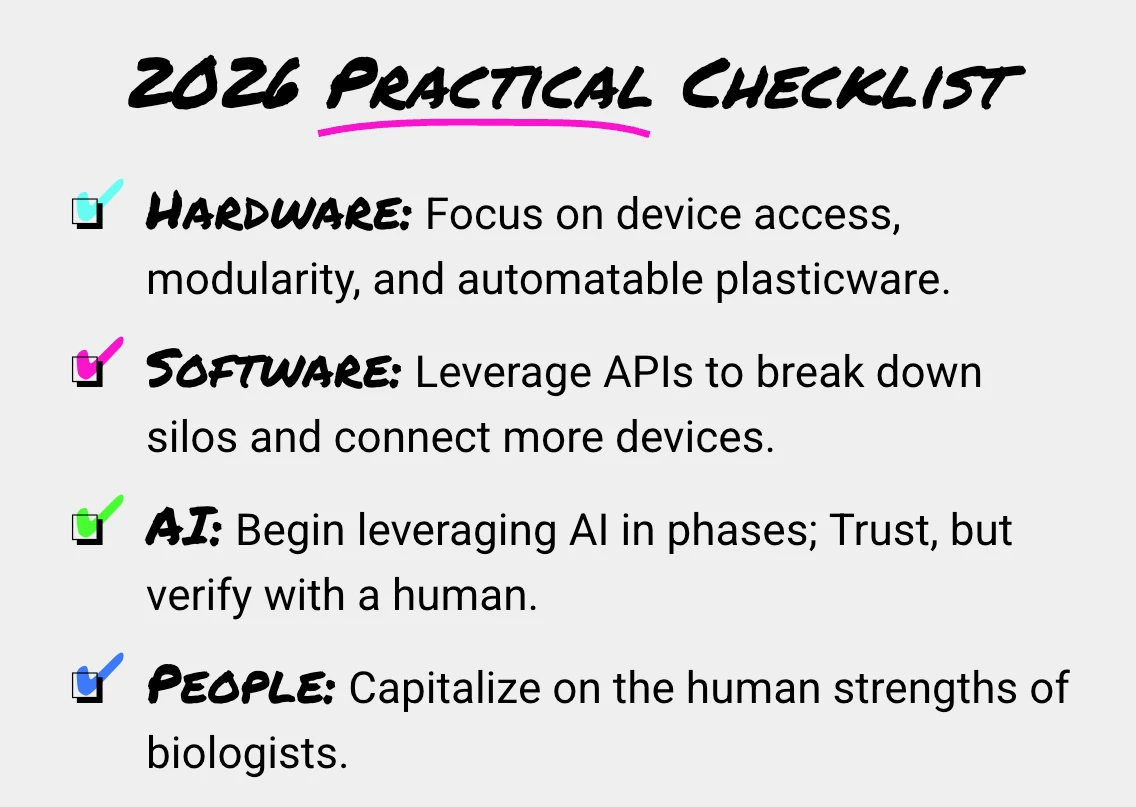

Even if you don’t have your sights set directly on a self-driving lab in 2026, the decisions made today about each of these four layers directly shape your ability to move towards full automation and self-driving labs in the future.

1. Hardware

Challenges

Hardware is not like software: it cannot be infinitely changed or customized on short notice, if ever. When you purchase a piece of lab hardware, you are often making a long-term investment. In many cases, you buy it once and own it forever. This can be challenging in a dynamic market, which is what we expect to see in lab automation over the coming years. For example, if your company pivots or your priorities change, there are serious questions about whether that device will still be useful at all.

Mitigation plan

- Physical access matters: In any autonomous lab, devices must be able to work with each other in the first place. If they can’t, then people will need to move materials between different devices used in the research protocol. It is critical to make sure that your devices allow for physical access inside their enclosures so the task it performs can be woven into the broader automation platform you will be building out. If other devices can access it, then its usable life will become much longer.

- Use automatable plasticware where feasible: Where economical, start using automatable plasticware. This kind of labware is usually more expensive, so you’ll want to focus on plasticware that will be fully used, rather than just one well of a 96-well plate. This will help you automate more of your processes over the long run, increasing your throughput and making integrations with other devices that support automatable plasticware possible.

Future-proofing

- Modularity and multi-purpose design: Newer devices—like the Trilobot—are coming to market that are modular and flexible. They support multiple tools within a single device, which is important because the same hardware can execute more critical tasks within the lab. Easily adding new tools and reconfiguring existing ones within modular robots frees up lab space, increases efficiency, and provides redundancy that helps ensure the device remains useful over the long run.

- Small form factor: We all know that lab space is limited. Plan for the future by choosing devices with the smallest footprint possible. Fortunately, new devices come to market every year with smaller footprints than previous models.

2. Software

Challenges

Picking the wrong software can quickly limit what’s possible in an automated lab. While GUI-based tools are often easy to start with, they may not support the full range of requirements in research environments, both simple and sophisticated. A lack of API access can also force manual intervention between devices, undermining automation entirely with siloed software that cannot integrate across the fully automated lab

Mitigation plan

- API access is critical: We cannot attain full automation without connecting our devices so they work together. While it might not be the most fun thing to build custom integrations, without API access, it will mean personally shuttling materials across your lab between devices. As a bonus, make sure the API uses a common programming language that many people are familiar with, including your own team, so you can hit the ground running and do not rely on a single team member to integrate devices.

- Granular control in the GUI: While this will not be possible with all software options, look for and, whenever possible, make sure your GUI-based software option gives you a way to access the deeper features and controls you want within the GUI itself, not just via API. This is a major time saver and enables faster build-outs and modifications of your lab automation platform.

Future-proofing

- Open, device-agnostic software: Even if we have an inkling, we don’t know exactly what devices we’ll have in our future labs. New and exciting products are released all the time that can either improve the current processes in the lab or add new capabilities entirely. To ensure it is usable in the future, make sure your lab automation is built on open, device-agnostic software that can easily integrate new technologies as they arrive. Nothing would be worse than discovering that a bespoke integration that only supports a limited set of devices has to be fully rewritten to leverage a critical new lab device.

- Automated data collection: Manual data collection is not only very time-consuming, it is also error-prone. Automating this step is not only useful for self-driving labs in the future and for feeding your AI, it’s also helpful in the short term by cutting down on the administrative work you need to do as a biologist. Make sure data collection is automated so you can focus on analyzing and leveraging the data rather than entering it.

3. Artificial intelligence

Challenges

As has been demonstrated in previous years, AI presents many opportunities for rapid discovery and optimization in biology research. However, AI also presents real risks to biologists and automation engineers: hallucinations and integration failures can significantly disrupt AI-led biology. And, with so many models available that perform many different tasks, it can be difficult to know where to start. AI can introduce distrust and add extra work if poorly applied.

Mitigation plan

- Primary literature research: As is the case with many things, start using AI in a bite-sized, easily verified way. We recommend primary literature research as a great place to start. AI can help survey the field and identify relevant publications during experimental planning, helping to educate you and inform protocol design.

- Data cleanup before data entry: While you may not want AI touching the data itself, AI models can be very helpful in formatting datasets to ensure consistency before upload. Data needs to be cleaned before entry, or you’ll need to write scripts to account for the mistakes that were introduced. AI can streamline this and save a significant amount of time

Future-proofing

- AI-assisted research protocol design: While closed-loop AI-driven research may not be in the cards for you this year, AI can still help design protocols at a high level for easy, guided creation within protocol design software. Instead of having AI generate code—and risk introducing errors that could destroy samples—use AI to interface with the higher-level parts of an experiment and inform experimental design. Let it help you think through the parts of the protocol that could be iterated upon subsequently to continue the research and development process.

- AI-assisted troubleshooting: If you have results and aren’t sure what they mean, or if you’re thinking about ways to optimize research outcomes, ask AI for suggestions on troubleshooting and protocol adjustments. Talk with AI the way you would talk with a senior colleague. Try it out on a protocol you understand deeply, like PCR. You may be surprised.

4. People

Challenges

One of the most pressing questions of our time is the impact that AI and automation will have on the workforce. This question is just as salient for the field of biology. While we cannot know the true long-term consequences, we are confident that the role of the biologist will evolve significantly as full automation and AI become more prevalent. Adapting to that change can be challenging for biologists and biology teams, both professionally and personally.

Mitigation plan

- Think like a programmer: To begin partnering more effectively with AI, start to think about your research in this way: “How can you turn your human protocols into objective functions with parameters that an AI can iterate on?” You may not have a self-driving lab set up right now, but you can prepare for this future by structuring protocols with variables that AI can programmatically adjust in a closed-loop system.

- Lab standardization plans and execution: Standardizing lab protocols is critical. It helps reduce inconsistency and errors, and it is also an important stepping stone to full automation and self-driving labs. Decisions about standardization make automating those tasks much easier down the line, and taking care of this now helps avoid double the workload (of both standardizing and integrating with AI) in the future.

Future-proofing

- Invest in your people: As the role of the biologist changes, there will be new areas to focus on that your team may not be fully prepared for. Invest in people and develop their skills so they can continue to adapt and meaningfully contribute in the age of self-driving labs. This can include training, evaluating new tools and technologies, and attending conferences to learn more about industry trends that can be incorporated into their lab.

- Focus on human strengths: Humans still have today, and will have for the foreseeable future, certain strengths that AI will likely not be able to surpass. When thinking about the important tasks for the people in your lab, focus on what people are uniquely suited for: synthesizing diverse information, critical decision-making about lab efficiency and planning (for example, requirements for samples and reagents), and addressing the needs of the people in the lab. Lean into these now and in the future.

- Leverage human judgment: AI may suggest or iterate in closed-loop research, but I firmly believe that a human must provide the final decision on critical matters to ensure alignment with ultimate research goals. Ultimately, a person decides what the self-driving lab is working on in the first place.

Making decisions today without closing doors tomorrow

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and for most biologists, their self-driving labs won’t be built all at once. They will emerge over time from many thoughtful decisions about their lab hardware, lab software, artificial intelligence, and biology teams.

By approaching decisions about these four pillars with intention, labs can continue advancing their science today while keeping the path open to more autonomous biology in the future.

If you’re interested in learning how Trilobio can support you in the transition toward self-driving labs, you can book a demo to see the platform in action. I’ll also be at SLAS 2026, booth #1239, and we’ll be doing live demos of our platform—come by and say hello!

Sign up for the latest insights and updates.

By providing this information, you agree to be kept informed about Datafold’s products and services.